In my previous post about Bitcoin and my thoughts about it, I have already covered some part of this journey through history: we have looked at the Roman Empire with its Denar and Aureus coins, we have seen how these once strong currencies degenerated beyond recognition in the centuries to come and what role the Roman emperors played in that.

The question, that now arises, is the following: was the case of the Denar and Aureus just a cautionary tale of monetary decay, or is this one example of a repetitive pattern? Best way to answer this question is to take a good look at other states and currencies.

The Islamic Dinar – Rise, Stability, and Decline

The Islamic Dinar was introduced by Caliph Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan around 696/697 AD (77 AH). The reform was driven by a desire to establish economic independence from the Byzantine Empire and to unify the vast Islamic Caliphate under a consistent, Islamic monetary standard.

The new gold coin took inspiration from the Byzantine solidus, but all imperial and Christian imagery was removed. Instead, the coin featured Quranic inscriptions, most notably the Shahada (Islamic declaration of faith), and was minted at a standard weight of 4.25 grams of high-purity gold (based on the mithqal).

Alongside the Dinar, a silver Dirham was issued, weighing approximately 2.9 to 3 grams. This continued the bimetallic system seen in earlier Roman and Persian monetary models, facilitating both domestic and international trade.

The Dinar exhibited remarkable long-term stability in both weight and purity during the Islamic Golden Age. It became a widely respected international currency, accepted across the Islamic world and beyond — from Europe and North Africa to India and Central Asia. Islamic banking practices such as sakk (early letters of credit) and cheques evolved alongside the monetary system, supporting a flourishing trade network. Cities like Baghdad, Damascus, and Cairo emerged as major financial centers.

However, with the eventual decline of the centralized Caliphate and the rise of regional dynasties, monetary unity unraveled. Local rulers began minting their own versions of the Dinar and Dirham, leading to inconsistencies in weight and purity. Over time, debasement eroded public trust. By the 14th and 15th centuries, European gold coins like the Venetian Ducat gained dominance in long-distance trade, gradually displacing the Islamic Dinar as the preferred medium of exchange.

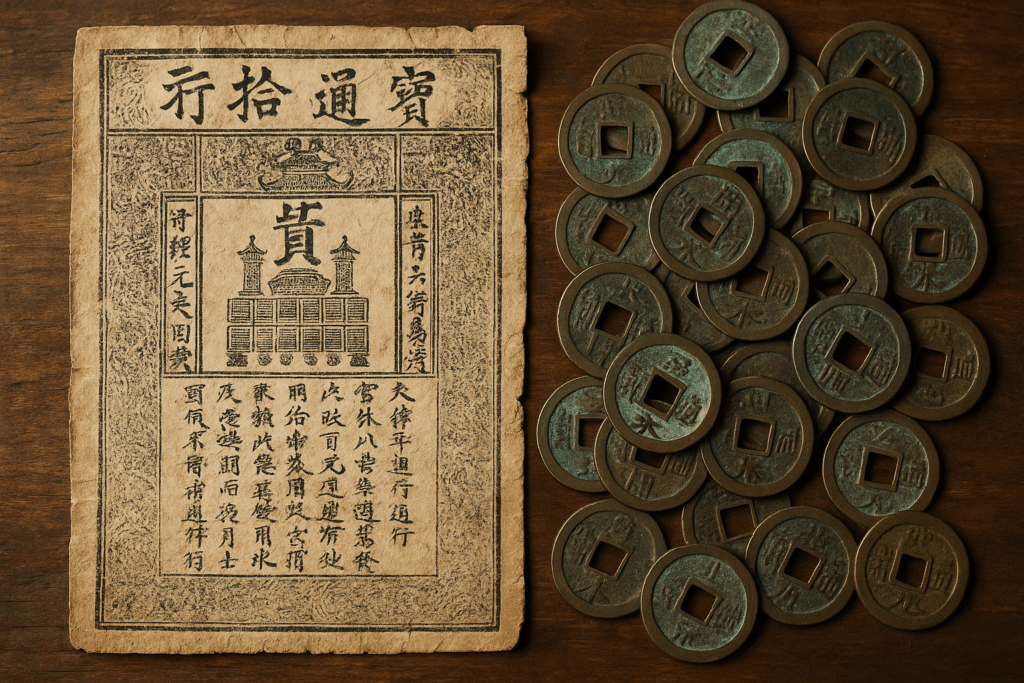

China – The First Paper Currency

From 618 AD to 907 AD, China was ruled by the Tang Dynasty. Copper coins, such as the Kaiyuan Tongbao, dominated the monetary system. Gold and silver were not used for daily transactions, but served primarily as a means of wealth storage and large-value exchange.

Through the Silk Road, China became deeply embedded in international trade networks, stretching from the Yellow Sea to the Mediterranean. However, the low intrinsic value of copper compared to silver and gold made it impractical for large transactions and long-distance trade — particularly due to the physical weight of transporting large sums.

To address this, the Song Dynasty introduced the Jiaozi around 1020 AD — the first officially issued paper currency in world history. This innovation was well accepted and functioned effectively for some time.

Later, under the Yuan Dynasty (1271–1368 AD), the Jiaochao was introduced and became the sole legal tender across the empire. It marked the first true fiat currency in recorded history — not backed by gold or silver, and not redeemable for precious metals. Its acceptance was mandated by the state, which initially ensured stability.

However, without intrinsic value or convertibility, the currency’s fate was sealed. Precious metals disappeared from circulation, and over time, inflation rose sharply. As confidence in the system eroded, trust in the currency collapsed.

The Ming Dynasty (1368–1644 AD) attempted to revive the model by issuing a new paper currency: the Da Ming Baochao. Unfortunately, it followed a similar trajectory. Excessive printing led to hyperinflation, and by the 15th century, the paper currency had lost virtually all value. China returned to a silver-based monetary system, and paper money disappeared from daily economic life for centuries — until its reintroduction in the 20th century.

One might say that China was the first:

The first to invent a fiat currency — and the first to suffer its failure.

Meanwhile in Europe: the Venetian Gold Ducat, the Spanish Real, and the Dutch Guilder

While China experimented with paper money and the Islamic world maintained a gold-backed dinar system, Europe followed its own path — defined by trade, city-states, and maritime empires. And with that came three of the most influential currencies in European monetary history.

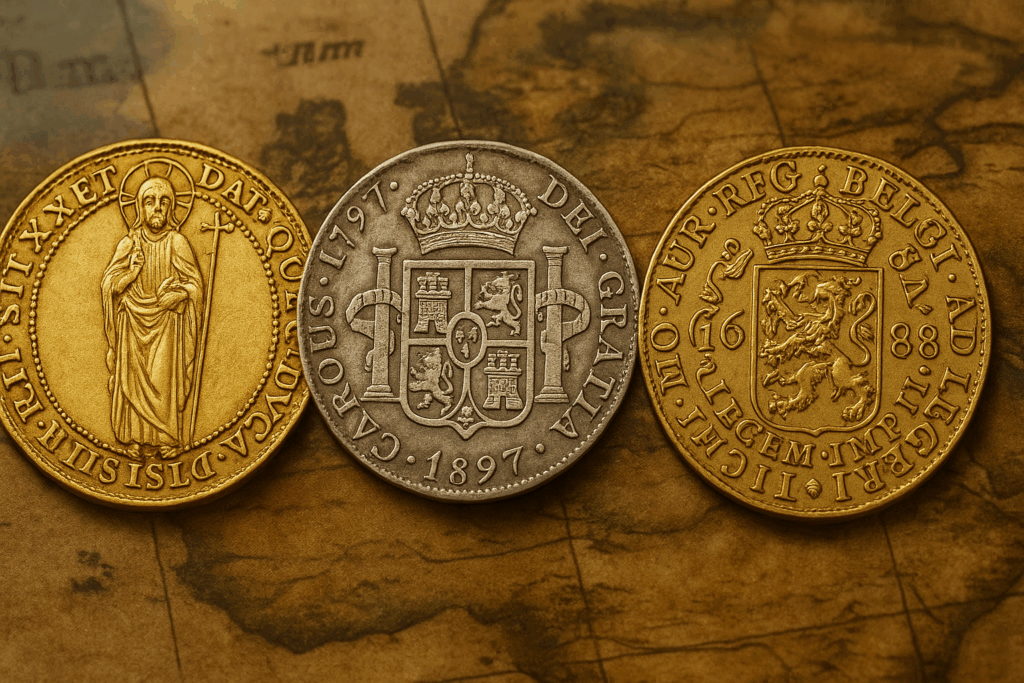

The Venetian Gold Ducat, introduced in 1284, quickly became one of the most trusted and stable coins in the world. Minted from 99.4% pure gold, weighing around 3.5 grams, it remained virtually unchanged for over 500 years. In a world where debasement was the norm, the Ducat stood firm — a monetary rock in the turbulent waters of European politics. Traders across the Mediterranean, the Middle East, and even parts of Asia accepted the Ducat without hesitation. It was, quite simply, hard money.

A few centuries later, Spain’s Real de a ocho — also known as the Spanish dollar — emerged as a global force. Originating in the late 14th century, the Real evolved into a standard silver coin that became the backbone of global commerce during the colonial age. It was the first world currency, accepted from the Americas to China. In fact, the modern dollar symbol ($) can trace its roots back to the Spanish Real. This coin moved empires and underpinned the early global trade system.

And then there was the Dutch Guilder. With the rise of the Dutch Republic in the 17th century, the Guilder (or Florijn) became the hallmark of fiscal discipline and merchant reliability. Backed by the booming trade of the Dutch East India Company, and anchored by the financial innovations of Amsterdam’s banking system, the Guilder helped establish the Netherlands as a global economic power. It wasn’t just a currency — it was a symbol of the emerging financial capitalism of early modern Europe.

Three coins. Three systems. All grounded in trust, metal, and trade — each reflecting Europe’s path to modern finance.

None of them were unlimited. None of them could be printed at will. All of them relied on scarcity, reputation, and merchant consensus. But like so many other currencies throughout history, these once mighty coins did not last forever.

The Venetian Ducat, after centuries of remarkable stability, began to fade as the Republic of Venice lost its political and economic influence. When Napoleon conquered Venice in 1797, the minting of the Ducat ended. Though the coin had maintained its weight and purity for over 500 years, political collapse brought its story to a close. Trust in the coin had never failed — but the system that upheld it did.

The Spanish Real faced a different kind of demise. While it had served as a global currency, the massive influx of silver from the New World — especially from mines in Potosí (modern-day Bolivia) — led to oversupply, inflation, and eventually debasement. By the 18th century, the Real had lost much of its original weight and purity. Spain’s growing fiscal problems, endless wars, and colonial overreach accelerated its fall. In the 19th century, the Real was replaced by the Spanish Peseta, and the global dominance of Spanish silver came to an end.

The Dutch Guilder survived longer — evolving into a modern national currency. It remained in use through the Dutch Golden Age, the Napoleonic Wars, and well into the 20th century. But in 2002, the Guilder was officially replaced by the Euro. Its end did not come through debasement or collapse — but through monetary integration. Still, the loss of monetary sovereignty marked the end of an independent tradition that had shaped Europe’s financial history.

Three different ends — but one common pattern:

No currency lasts forever. Not even the most trusted ones.

And Then Came the British Pound… and the US-Dollar

As the old trading empires faded, two new powers emerged — Great Britain and the United States. And with them came two currencies that would shape the modern world: the Pound Sterling and the US Dollar.

The British Pound, one of the world’s oldest currencies still in use today, gained international prominence during the 18th and 19th centuries, as the British Empire expanded across the globe. What set it apart was the introduction of the Gold Standard in 1816, which formally tied the value of the Pound to a fixed amount of gold (~113 grains of pure gold, or about 7.3 grams). This gave the currency stability, credibility, and global trust — qualities that made it the preferred medium of exchange in international finance throughout the Victorian era.

London became the financial capital of the world, and “Sterling” became synonymous with trust and solidity. For much of the 19th century, global trade settled in Pounds, and British banks set the tone for international monetary policy.

Across the Atlantic, the United States had adopted the US Dollar in 1792, with early silver and gold coinage designed to mirror the widely trusted Spanish Real. Like the British system, the US also moved toward a bimetallic standard, later shifting to a de facto gold standard by the 1870s.

By the end of the 19th century, both the Pound Sterling and the US Dollar were gold-backed, globally accepted, and widely seen as the pillars of modern monetary order. They enabled industrial expansion, global trade, and cross-continental investment.

But even then, the seeds of fragility were present.

Because history had shown it many times before: Stability built on gold can last — until it doesn’t.

We have seen empires rise and fall — and with them, their currencies. What came next was different: A new century, two world wars, and a global financial order unlike anything before. We will cover this in the next post, when we turn to the 20th century. But even then, the old pattern continued…